There is no more of a direct way to start this piece except to say that violence against Asians needs to end.

I’m learning to listen as the Asian community grows more outspoken of its silent plight. An increasing amount of random racist attacks against some of the most vulnerable elders in the community has made me contemplate why this fight feels so familiar, yet…unique. I won’t pretend I know their struggle or that the uphill climb is one we as African Americans have already trekked. A disproportionate number of blacks being hunted by police cultivated much of last year’s dialogue, but in the backdrop, the world was also learning about the expensive myth called the “yellow peril”—leading to the attacks and killings of those in our Asian communities. So much so that we are now recounting how many were struck with every “Kung Flu” or “Chinese Virus” epithets cavalierly uttered, in part, thanks to Donald Trump.

A total of 241 African Americans were shot by police in 2020—while the AAPI community reported a 149% increase in hate crimes. The racial plight of these two minority groups had not been conflated and it seemed obvious why. The day following the shooting spree that resulted in the death of eight people (including six Asian women), an Instagram commenter aired his frustration at the lack of a similar visible outcry matching that of George Floyd’s murder last year. Why weren’t people marching angrily in the streets, having deeper conversations on all medias, breaking windows and setting the world on fire?

My response: the active, slow or accelerated extermination of any group targeted for their nationality (or religion)—out of the stinging act of oppression is always horrible. But the experiences of the hate in the Asian community and of that in the black community is not one in the same. And I told the commenter—he shouldn’t want it to be. A common trope seen in the past weeks as actors like Olivia Munn and Daniel Day Kim addressed in interviews: this is the BLM movement for the Asian community. The Black Lives Matter movement and the AAPI movement are both fighting oppressive racism—but that’s about the point commonality stops.

During an interview with Monthanus Ratanapakdee, the daughter of Vicha Ratanapakdee—an 84-year-old Asian man who was randomly attacked in San Francisco—she and her husband, Eric Lawson, sat with Nightline to discuss his later passing from the injuries he sustained. My own feelings of sadness for her father’s experience were abruptly thwarted when Lawson—who did not appear to be Asian—looked at the camera and demanded that black people needed to talk to their own—because his father-in-law’s attacker had been black. And yes, that ignorant statement was offensive.

I’m an African American woman and I don’t associate with anyone who would commit any such violence towards anyone for any reason. There is not one black person in my vicinity that needs a talking too. And there came the epiphany: there is no one group the Asian community and its allies can decry. A pickle the Black Lives Matter movement does not quite face.

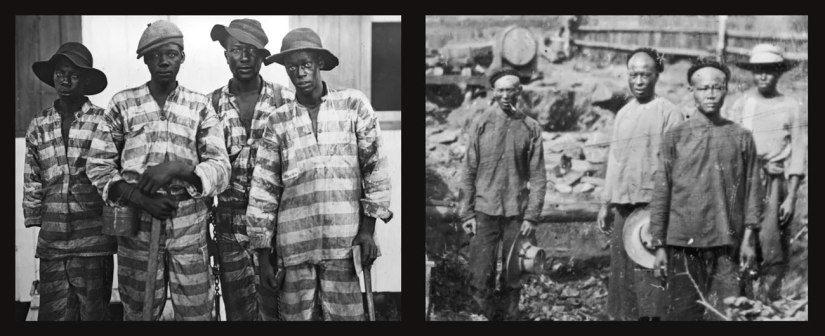

Police departments were the primary object of the 2020 BLM protest. A distinct history of the brutal oppression from the moment Africans were brought to America as slaves. Floyd’s murderers were all former cops which means they were formerly employed by an organization whose original function was to capture (and at times kill black slaves). As allies to the BLM movement, we spent the summer attempting to shake the white supremacy out of an institution who’s had racism running through its veins for nearly two centuries.

We needed higher regulations for police officers and politicians to be instinctually competent enough to see the conduct of policing—and to put themselves in the shoes of average citizens instead of fully armed officers who commonly claimed they killed because they “feared for their lives”. How infuriating would it be to hear the Atlanta shooter claim he shot those eight people because in the course of getting a massage, he thought the masseuse was reaching for a gun when she was reaching for lotion. And how angry would anyone feel if they knew his viable defense was “he feared for his life”.

I am somewhat aware of the relationship between the Asian community and police, but there is something far more nefarious and disunited cornering the Asian community. As addressed in an article by University of Colorado Boulder professor Jennifer Ho, titled White Supremacy is the root of all race-related violence in the US, this is a white supremacy issue—even when the violence is carried out by the black and the brown. You don’t have to be white in order to do something in the faith and name of white dominance.

It’s so easy to start comparing battle wounds of the respective cultures, but that involves attempts to downplay the hardship of one versus the other—and it’s not productive in this battle. The AAPI movement needs to be its own battle for equality that we fight together with the Asian community.

The anxiety felt by Asians, both in this country and Canada is palpable—not only being consumed by one’s own safety but of the safety of their loved ones. I too have grandparents whom I worry about the welfare of when I’m not with them—so I get the fear. I’ve also had to file a restraining order against an armed and active police officer, who had plenty of armed an active colleagues resolute in reminding me that if I scream, no one will believe me. Basically—I get the terror.

Mr. Lawson’s misguided request had actually been on my mind long before his families’ loss. 2020 had left me more discombobulated than ever regarding the lingering support for Trump. Not just for his failures in the handling of COVID and every other initiative bungled, but for his racial rhetoric—particularly in the rare moments I encountered a minority voter. Living in California, most of these encounters were left to social media where one day last fall, I found myself in a verbal tussle with an Asian Trump supporter. When asked why she would stand for a man who clearly thinks so little of her community that he’s willing to put a target on her back, her reply had been that Trump was not talking about her. When I decided to turn Trump’s rhetoric on her, her argument eventually rescinded. Perhaps Mr. Lawson should have a conversation with her.

Asians represented 31% of the Trump vote in November 2020 (and 12% of the black vote)—slightly higher and sans the virus vitriol in 2016. To some, this may have been an act of simulating rather than solidarity. Had Trump’s one attempt at squashing anti-Asian rhetoric not tested so poorly with his mostly white audiences, an emphatical and consistent stance to protect the Asian community from backlash could have saved those falling to the other race reckoning happening in our country. When a former QAnon supporter had been asked by CNN what would have steered her from falling down the disinformation rabbit hole, she replied that a staunch denouncement by Trump would have stopped her from following the platform.

Whether Trump should be the subject of a major lawsuit by the AAPI community or if we are just merely the long haulers of his four-year hate train, the Asian community deserves to know the root causes of these elevated hate crimes.

Every time a new attack is publicized, my first question (after the nature of the attack and the welfare of the victim) is why the person did it? It’s a loaded question but it concerns me that this isn’t questioned by the media (and possibly law enforcement) fast enough, and that advocates are not dwelling more on it—the identifiable pattern.

When two elderly people were attacked in March in downtown Oakland by a homeless male, these details were glossed over during an interview with the attacker’s public defender. He indicated his clients need for a psyche evaluation because the man appeared mentally ill. This was a secondary question to the reporters more pressing query of how the lawyer felt about representing the defendant when he, the lawyer, was in fact Asian.

Intrinsically, I always look for the existing pattern—but stop short of creating one when there may, in fact, be none. My frustration with every nonsensical attack is my commiseration with Mr. Lawson. There is no point to any of this. But just as actor Daniel Dae Kim retorted, it is clearly not just a singular race supremacy issue but mental and possible environmentally grown hate. I think the AAPI community is acting logically by proactively stepping up, and not stepping back, their fight.

I don’t feel, see or believe that there is some profound sector of the black community that hates Asians but if we’ve learned anything from the demographics of Trump supporters, ignorance and racism comes in all sexes and from all origins. Still, it is incredibly hard to see these attacks manifest.

I live in the state most populated by the AAPI community and have certainly grown up in ear shot of racist utterances—but I’ve also grown up understanding the common sense of treating people as you wish to be treated. As I write this, fully vaccinated—I reflect on the singular incident in this past year when I’d received a vile reaction for sneezing in public. It was from an older Asian woman—who jerked away from me with a glare. I remember physically visiting an Asian professor of mine who swore people missed his class out of laziness to prove to him I had contracted laryngitis, causing him to scowl from me with an accusation that it might be Sars. A reminder, I’m African American!

It has been easiest to not have a categorical opinion of the Asian community, and that for me is the best resolve. I have dealt with racism and some of that has been from Asian individuals. I hadn’t realized how color blind I had been until it recently occurred to me while in the process of working on my first book. That while my rapist was not of Asian descent, every other incident of assault or sexual objectification I have been subject to has been by Asian (non-Indian) or bi-racial Asian men. The realization doesn’t draw me to hate or aggression—but cognizance. While I do not have Asian kin nor are any of my close friends Asian, I do work and live alongside great people, some of who are this targeted race.

It brings to thought that the issues are not cookie cutter but what is currently happening to the Asian community is out of bounds. An alarming amount of these attacks have been committed by black men and though astounding, I can relegate that these are individuals who do not grasp or see the hypocrisy in their racial intolerance rather it be out of mental instability or otherwise.

The Asian community has shown up tenfold for the Black Lives Matter movement, and the rest of the country should do the same in return. For myself—I will pledge to stay vocal when prejudice is in my vicinity during any act of hate. For we have faced similar acts of historical massacres, racially discriminative laws, and hate crimes without adjudication. So where will we march for the AAPI community? Who are we marching to? Are we screaming to the heavens?

While I look forward to the apprehension of every perpetrator committing hate crimes against Asians, the swift arrest and charges leaves me heart sick and fatigued for the road ahead of the black community. That homeless man who was arrested for attacking two elderly Asian people in Oakland will be prosecuted. Robert Aaron Long, the Atlanta shooter will never see the light of day again. While the AAPI community is calling for the recognition of hate crimes in these cases, we are crossing all extremities hoping a Minneapolis Police officer will see a prison cell for murdering a black man over a counterfeit twenty dollar bill. We don’t have time to protest the lack of a hate crime charge against Derek Chauvin, we were too busy protesting for him to be apprehended from his living room couch. This is the pickle of the situation dominating the lives of the black community—that we can stop seeing police officers get the treatment once afforded to the killers of Emmitt Till. This is why one thing is not like the other.

And just as with the recent killing of Daunte Wright, I think it is important that charges stay within the imperfect system of laws and prerequisites we require for such charges to be applied. I do fear that through this, some will be pushing a square hate crime peg into a first-degree murder hole if the required evidence isn’t there. This could prove to be a double-edged sword—in any case—and in any society where prosecutors follow public pressure, and not the law, to administer justice. Profound emotions of injustice should create more just laws, not pressure induced charges.

Though I do believe Trump and his (in)ability to understand such complex tropes as the Kung Flu “Gina” virus will pass in the heap of Alt-right conservative history, he has certainly lent vocal freedom to those who harbored such closeted prejudice as if it has been a continuous four-year celebration of Festivus. A line from a skit of The Chappelle show called “Clayton Bigsby, The World’s only Black White Supremacist”, has echoed in my head from the beginning of Trump’s presidential campaign: “If you got hate in your heart, let it out”—a mocking dig at the core of white supremacy. Well Trump has certainly become an idol in the eyes of hate.

I pledge to do what I’ve always done during the commission of a crime, intervene and aid as I would hope others would do for me.

With that said, I wish the utmost safety and support to the Asian community worldwide. The AAPI community has the right to a reckoning all their own.