ON MAY 25th, San Jose, California became the setting of the 15th US mass shooting in 2021 where nine men were killed in the Valley Transit headquarters located in northern District Victor, after the shooter, Sam Cassidy, set his home ablaze in the central southern policing district of Lincoln. Mass shootings are quickly becoming the crop circles of our time—in which we wonder when and where—not if—and by whom they will occur. Within hours of the act, the FBI, ATF, and local police put a mic’d podium on the world’s stage—a concrete divider centered along a main street amongst the maelstrom, their suits certifying the dire moment.

Then. A sexagenarian, blonde woman slowly creeped out amongst the forest of men, adjusted her sheriffs’ uniform (gold stars and all), and took over the grand stage. I turned off my computer. Nine people had died and I wanted to feel the moment, but to those in the know, bad cops become gnarly distractions to such tragedies, or such tragedies serve as timely mischaracterizations for bad cops.

The six-time elected sheriff of Santa Clara County, Laurie Smith, has been the center of campaign contributions controversies (in which the undersheriff and a captain have been indicted by the Santa Clara District Attorney, but Smith has not), alleged past sexual harassment allegations and under her watch, a mentally ill homeless man was beaten to death in 2015 by three deputies who are now serving fifteen years to life prison sentences each—in addition to behind the scenes shenanigans better saved for another article.

She’s appeared on the Investigation Discovery Channel’s See No Evil and Web of Lies, where department heads are typically not interviewed to rehash investigations they did not conduct—the self-interposed Smith had sincerely become too much for me. A woman known to show one face to the world—and another to her department walls, I feared her public lack of humility would turn this moment farcical.

Smith is a Michigander from the Mitten, a republican, and after years of questionable transgressions—both morally and monetarily—she is yet again the focus of polemically laced calls by officials for her resignation over county jail conditions.

Ultimately, Smith’s failures are the fault of those who continue to vote her into power cycle after election cycle. Hers’ is a political position and as constituents, we don’t seek ethical leadership—come election time, we want to be “mind f*cked”.

After ten years of studying police behavior, I’ve learned to keep officers like Smith in perspective, necessary when in possession of a queasy stomach. While Smith is not an officer I’ve researched, she is evidence of the involuted and not so black and white makeup of law enforcement the country is now daring to simplify and solve. I’ve met a lot of bad cops. Nothing about police officers is straightforward or categorical.

I too once believed in the ataraxia inducing sales pitch of the ‘good cop/bad cop’ myth, growing up around a police department, the good cop was every cop I knew, but in hindsight, there were signs. Perhaps I had been too advantageous to realize that officers like Smith were complicated, therefore convoluting the profession.

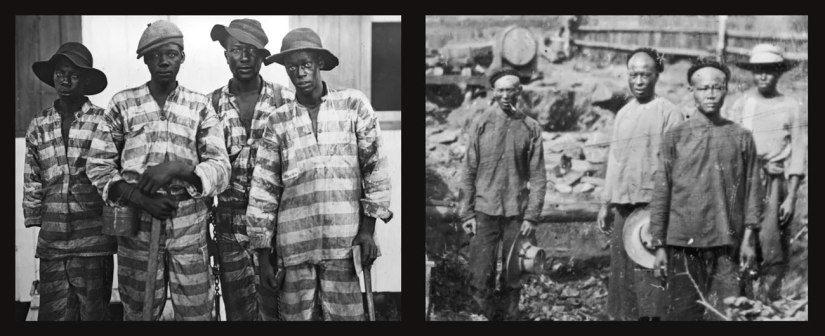

The past year has been a looking glass into this uncategorical institution where we watched former Minneapolis police officer—and lynch by cop murder defendant—Derek Chauvin, meet an all too rare judgement where for centuries, white men had been acquitted by predominately white juries for similar crimes.

Even as George Floyd’s slow death played on loop, we learned how defensible cops were as Floyd was continuously (and still in social media today) put in the defendant’s chair—while Chauvin’s previous conduct, which includes, but is not limited to the beating and choking a teen boy—somehow seemed not so bad. The sympathizers of Chauvin and his gang of four highlight the realization, that to some in society, an officer’s crimes will always be deflected by the shiny badge—relying on a dire reality: look deep into their eyes and you’ll see the soul of every American cop.

While weaponizing public trust is nothing novel for police, blunt double standards and the inability to envision or comprehend a higher quality of policing in this country has been our handicap. Floyd’s death moved the goal post to end the nucleus of police misconduct: qualified immunity—but the conservative parties’ involvement (who’s made Back the Blue a party trope) has made the remedy just about as cloudy as the problem. Who knew things would get complicated on January 6th?

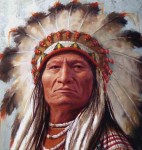

We saw an act of terror on the nation’s capital, as footage of uniformed police were seen beaten by crowds containing white supremacist, as well as current and former military and police such as Karol Chwiesiuk and Alan Hostetter, marching united under the MAGA umbrella—striking blows with polls fastened to blue lives flags. Outsiders were front seat for this unforeseen domestic squabble: Blue Lives mattered until right wing politicians perceived the actions of the capital police—defending the capitol against their mobbing constituents—as an act of (police) biting the hand that kept them feed. Yet the recent talks of police reform show republicans can’t relinquish dreams of a racially oppressive vestige—indemnity free policing from days gone past.

On MSNBC’s The Beat with Ari Melber, Marq Claxton, who is the director for the Black Law Enforcement Alliance, had a disassembling thought on the phrase. “Blues lives are Smurfs. It’s never been about police lives or that blue rhetoric, and the blue wave really. It’s all about something other than respecting the law and order and sanctity of life, etc.” The former NYPD detective continued, “what this has been all about, and continues to be about, is a political movement trying to pull in as many of these so-called blue-collar workers—in spite of, and this is what amazes me about police—they tend to rally around these blue lines nonsense things, in spite of what we’re seeing here [the testimony of capitol police], where often times these same people who are promoters of everything blue, have turned their backs on you.”

Discombobulated yet? Police are without definition in a current time where some department heads seek to shed the very roots of white supremacy it once sprung from. They’re like the hive mind alien, Unity, from Rick and Morty or a profession filled subterraneously with those who read to many Judge Dredd comic books in their youth—but for now, there is no clear comprehension of policing amongst the malleable public and those whose vision and scrutiny derive from personal encounters or regular consumptions of COPS, Live PD and PAW Patrol as the litmus test for how things should have ended. I get annoyed when people think it’s that simple.

April 20th of this year marked the tense delivery of the Chauvin verdict and the police shooting of a 16-year-old girl in an Ohio suburb.

I imagined the protesters, war torn from a year of constant battle cries, grabbing signs from their closets. It was the first time the impulsive marching felt vacuous and risked devaluing the movement of justice without a review of the facts. Studying San Jose police calls made body camera footage immediately released to the country by the Columbus Police Department seem more quizzical, than anger provoking. My disdain was suspended by the question of what and why?

What did the dispatcher tell the responding officers? Had there been prior contacts at this home or with the phone number 911 had been contacted from by Ma’Khia? What information had been relayed to the responding officers? Were officers told it was a group home? Based on the information—or lack thereof—should the officers have 87’d (aka: met) at a location a distance from the scene and strategized before engaging?

Was the shooting officer, Nick Reardon, and his department members equipped with less lethals? And what of a subduing Taser? Would Bryant’s fast movements preceding the arrival of the first officer had prevented the prongs of the Taser from contacting her skin? What if her clothing had been too thick? Would the surge of adrenaline or possible undisclosed narcotics in her system prevent a fast enough effect of the Taser to stop her from stabbing the woman in pink? And at that point, how many punctures would Bryant had achieved? And why do we see a grown man kicking the first subject Bryant rushed to the ground.

Her sudden charging towards the officer and the two perceived victims provoked the officer to pick the life of one black woman over another. The shooting is now a part of a DOJ investigation.

This is a far cry from video released this past summer of Ronald Greene who was savagely beaten and murdered in 2019 by Louisiana State Troopers—ego bruised by a man who dare lead them on a chase probably dangerous enough to terminate. He was tased, beaten, choked and dragged face down across concrete by an officer who would later brag about the attack. Then delivered to a hospital handcuffed and dead, where medical staff had been told he’d died in a crash. The district attorney belying the facts of his death.

What I would say to those who wish to see an amalgation of Bryant’s death with that of the murder of Greene is this: If you can’t instruct an officer how to better handle a situation, then you can’t instruct. And as much as some officers would like to be viewed as super human, they in fact are not. They don’t host police academies at Hogwarts School of wizardry—no wave of some magic police baton can make for a petrificus totalus.

To be clear, sloppy policing by sloppy officers is what leads to the death or maiming of citizens lacking due process.

With that said, Ma’Khia Bryant was a child of the state who left the world judged by a system that had long failed her.

The general consensus is to spend brain power and town hall discussions theologizing officers like those I’ve researched—those who braggadociously label themselves as Waste Management for the city of San Jose. As well as Derek Chauvin or the mistress of Santa Clara County herself, Sheriff Smith, and every other cop across this country—when perhaps police misconduct can be whittled down to a simpler reality: bad people treat people badly.

Blue walls. The Force. All terminology I’ve grown to hate, but if the blue wall is your cup tea, then let me introduce you to some of the bricks.

Misconduct: The Jon Koenig Way

Leveraging power over of others (and sparsely unchecked thanks to qualified immunity) by way of a superior authority can appeal to those unable to achieve such validity in a normal life—as so I’ve learned, can be the dangerous sell of a career in law enforcement.

Researching a police department—unfiltered—is like entering the jungle where humanity is altered—hunting, mating and socializing tactics feel transmuted due to conditions of the “brotherhood”, where officer conduct is typically contrived, banal and non-divergent out of survival amongst their fellow blue. I’ve spent time with officers who’ve made my skin crawl, and a small few who were genuinely good guys—but I certainly left a little bit of myself behind while covering this story. Importuned and determined to finish a cultured journalism degree—I was educated on police statistics instead of stereotypes, an overview on what domestic violence is when your partner is a cop and sexual assault culture—eventually making me the target of threats from the San Jose Police.

These words are anxiety laced as I now understand the blue wall and mortar holding it impenetrable. But here are the facts:

My research into police calls began in July 2009, and concluded on schedule in December 2019 just as the first officer who kicked off this story, sergeant Lyle Jackson, who was 13 years into his tenor with the department when he first approached me—was concluding his career with the department.

I knew from my first outing with Jackson, that there was a story. It is impossible to report on every officer and every department in the country, so I chose the statistically route. A sample group of officers then grew out of whom ever wandered out of the woods and into the circumstances, throwing his badge into the pot—and with every addition the story branched further. It’s been a cathartic racing of the clock as I am legally tied to SJPD for 2 more years and 10 months, Dua Lipa’s We’re Good playing as I send each chapter out for edit. As a journalist, the biggest lesson I’ve learned out of this is to trust the process. It is through officers like Jonathan Koenig, one of six officers being profiled, that I became educated on how bad cops not only thrive, but survive in US police departments. I was a neophyte penning a compendium love letter of sorts to the evils of law enforcement. And one pivotal rule of journalism is to know your subject.

The sample group is composed of 135 San Jose Police Officers. However, two more SJPD officers were added in 2020, and another two were added back to the list after previously having been disqualified (Officer Blanky Cruz and Sandra Sandez, who’d perished from brain cancer in 2018, making her the only dead officer on the roster).

Thirty-one of the officers have retired and two have been fired. Fifteen left voluntarily—and of those, two have returned. Eighteen are women. Sixty-six of the officers (including Alan Coker, Justin Horn, and Billy Wolf) are white or of European descent. Twenty (included officers Jonathan Koenig and Larry Situ) are Asian. Thirty-eight officers (including Mike Ceballos and Jose Martinez) are Hispanic. Eight officers (including sergeants Ray Vaughn Jr. and Lyle Jackson) are black. At least three are open members of LGBTQ+ community.

At least nineteen officers have either shot someone or have been accused of excessive force. Two have been arrested (for neither of the previous offenses mentioned). Twelve come from previous departments. Three are former dispatchers. Eleven have confirmed military backgrounds. One is a former elementary school teacher while another 2 officers teach at local junior colleges. Twenty-nine have four-year degrees, while one has a juris doctorate. Five of the officers were known to me personally before the start of this story.

I’ve witnessed shocking things and have been impelled into acts I will never let happen again. I’ve actually been asked by a sergeant why I didn’t tell an officer NO!

The caveat is overtime, ‘Were not all that bad’ stops being thrown at you like a sitcom tagline once officers know you’ve seen too much—a blue curtain drops in its place.

Police continue to be a darker conundrum armed with artillery, monopolization of safety, and the weaponization of gaslighting. The devil you know. Publicly lauded as societies sanitation while void of dignification. Poster boy heroes with their fright night tactics, somehow fails to retain a classification other than necessary.

Four days a week, SJPD officers drive upwards of an hour to avoid, in plain clothes, the citizens they serve, protect, harass, and occasionally kill in uniform—to park their car in a lot and cross a two-lane road into a brick-and-mortar department, where for 10 hours a day, they can live an alternate existence from their normal daily lives—either for good or bad. I have plenty of battle scars from my time studying the department but as a journalist, it was never the plan for these marks of war to stay in my custody.

The lowest badge numbers in this study (at the time of this publication) started with the SJPD in 2013. Bad cops are leaving but statistically, plenty more are arriving to take their place. And while studying police behavior and habits won’t stop more imbibed into a profession fit for the outliers, it will help gain better protection from the entire herd, Sheriff Smith and those alike.

This article ends with officer Eddie Chan, badge #3735. A problem cop who joined my study in 2013. Whose buffoonery earlier this year landed him an internal affairs quarry and a spot on the eleven o’clock news in a video where, while swinging a police baton to a Mortal Kombat theme in his sergeants uniform, managed to degrade his embattled profession while simultaneously aggreging Asian stereotypes at a time of already elevated racial tension in the Asian community. This is an officer SJPD has worn the behavior of proudly. Chan will be covered in a future blog post.